A White Paper1 for High School Educators – July 12, 2022 (updated)

As teachers of Health Education and of Family and Consumer Sciences courses, we are adept at “teaching on a tightrope” when it comes to educating teens about reproductive and family health. We walk that fine line between providing enough knowledge to help teens make informed choices, still encourage abstinence, while straddling the realities of teen sexual risk-taking. In recent years, birth rates for teens have dramatically decreased. We can thank sex education, availability of contraceptives, and changes in teen behavior for this improvement.

But now we face an urgent situation. Seismic legal changes are underway that are likely to significantly restrict availability of many family planning services and some forms of contraception. Regardless of anyone’s stance on these controversial issues, we can anticipate serious health and legal consequences. Teens, who are by nature risk-takers and impulsive during this stage of life, will be at the greatest risk of experiencing an unplanned pregnancy and least equipped to cope with the consequences.

The legal landscape will be fluid for the next couple of years. Lawmakers and judges at state and federal levels will be debating and creating new rules. There will be appeals and reversals. Effects will ripple through our health care system, our social norms, and ultimately high school education standards and policies. There are a lot of important issues that have yet to be clarified!

So how do we guide students during this volatile time? What changes should we consider making in our approach to teaching about reproductive and family health?

No doubt, students will have many questions, and it will be challenging to provide clear answers with so many diverse public opinions and legal matters in flux. Although side-stepping is one approach, as teachers we don’t want to inadvertently suppress students’ natural curiosity and learning. We certainly don’t want teens stumbling ill-informed into situations that could affect their life trajectory.

What needs to change in our teaching approach is to recognize that teens urgently need our guidance about why it’s important to responsibly handle romantic encounters and avoid an unplanned pregnancy. Prior to discussing methods of pregnancy prevention (aligned with school policies for sex education), there needs to be an emphasis on understanding the big picture and identifying personal motives for postponing parenting until adulthood. Motives before Methods.

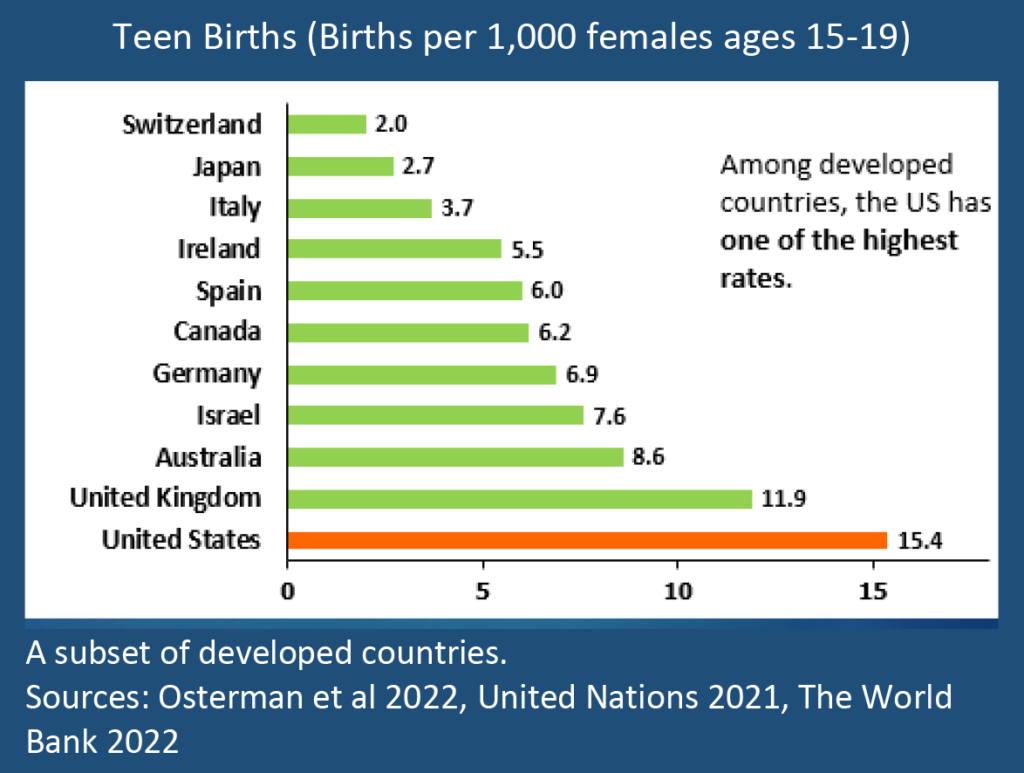

So let me take a moment to explain why motives are so important, before sharing our 7 Timely Tips. It’s related to a fascinating phenomenon of U.S. teen birth rates being several times higher than almost all other developed countries. Even with dramatic declines in teen birth rates, this disparity has persisted.

Researchers have long been curious why U.S. teen birth rates are higher than other developed countries. Interestingly, they find the difference is not explained by levels of sexual activity, but rather U.S. teens use contraceptives less reliably (UNICEF 2001, Guttmacher Institute 2002, 2014). Among many potential factors, two rise to the top: “[Most teen parents] say they did not know enough about either contraception or the demands and difficulties of childcare, and they wished they had waited before starting a family.” (UNICEF, 2001)

Now, with family planning resources becoming less accessible, it’s crucial our teens are motivated to take steps to prevent an unwanted pregnancy. When one is unprepared to care for a child, it can lead to child maltreatment or sometimes the hard choice of releasing a child for adoption. These situations can be heart-breaking for everyone involved. Although some people note a “shortage of adoptable babies,” there are over 400,000 children in the U.S. foster care system whose parents are unable to provide adequate care. Additionally, in 2019 alone, child abuse and neglect referrals were made to Child Protective Services involving 7.8 million children! (US DHHS 2021) Helping teens plan ahead for the parenting stage of life can motivate them to be proactive now and better prepared later.

At Educate Tomorrow’s Parents, we have developed some teaching strategies to help teens make informed and responsible choices about when and how they form a family. Our nonprofit has been conducting our Healthy Foundations for Future Families program in a variety of states, cities, and schools since 2005. As a result, we’ve honed guidelines that keep the teens’ futures front of mind, and also comply with school district policies for reproductive health education. These tips may be especially valuable now that some educational policies may be in the process of re-evaluation.

Focusing on preventing the circumstances that lead to unplanned pregnancy, we have found common ground across a spectrum of personal and philosophical opinions. We use an approach that empowers students with scientific knowledge and vocabulary, helps them explore philosophical and legal perspectives, and ultimately guides a teen to align their actions with their life goals.

7 TIPS FOR INSTRUCTING ABOUT REPRODUCTIVE AND FAMILY HEALTH

1. Center the lesson within each teen’s hopes for a strong, healthy family.

Create time and space for each student to envision their dream of family, respecting cultural and personal differences. This vision becomes their North Star, and a context for considering whether current behavior choices are on a path leading them towards or away from their goals.

2. Explore the responsibilities and resources needed to achieve their strong family.

Build teens’ knowledge of the 24-7 responsibility, costs, and 18-year legal obligation to care for a child. Enhance their motivation to wait until adulthood by examining the challenges of teen parenting and guiding them to craft a plan for acquiring valuable life-skills and resources.

3. Provide scientific information about preconception health and prenatal development.

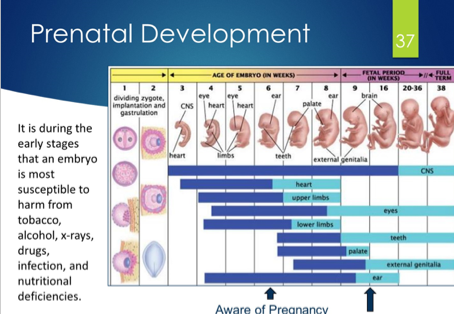

- We know that life is a continuum; life comes from life. Way before pregnancy, people’s bodies have the key ingredients (eggs and sperms) for creating future generations. A person’s health habits prior to conception can affect their future child’s health.

- We know the stages of development after an egg is fertilized by sperm.

You can use a commonly-used chart, like the one below, to describe the development process after conception:- from zygote (a single cell)

- to blastocyst (a collection of cells)

- to embryo (cell differentiation for organ structure)

- to fetus (organ development, begins at 9-10 weeks of pregnancy)

- ultimately to a newborn infant.

Here’s a wonderful online resource from the Merck Manual Consumer Version that describes the developmental stages: “Stages of Development of the Fetus”.

You can also use the DVD video “In the Womb” from National Geographic which is available on Amazon.com.

4. Acknowledge the limits of scientific knowledge in defining “fetal personhood.”

Making this distinction between facts and beliefs can help maintain neutrality on controversial topics. When students are exposed to diverse opinions, they can appreciate the complexity of our current affairs, and may have greater motivation to avoid unplanned pregnancy and all that may entail.

- We aren’t able to scientifically identify when a fertilized egg becomes a “person.” That is a philosophical question and the answer depends on one’s perspective.

- (If permitted) Encourage students to respectfully explore different ideas about when a fetus becomes a “person,” referencing different cultural, religious, and legal perspectives. For example: Does “personhood” begin at conception as a zygote? or as an embryo before it has fully functioning organs? or when the fetus begins moving (around 4 to 6 months)? or when the fetus can be viable as a premature delivery (beginning around 24 weeks / 6 months)?

5. Explain the boundaries of what you are able to cover in a class setting.

If a question is outside the scope of the lesson, won’t fit in the time available, or not included in current course standards, you can share those constraints with your students. When they know why you can’t answer their question, they will feel respected and free to seek answers from other sources.

6. Emphasize the importance of planning ahead for the timing of a future family.

By helping teens realistically plan when, or even if, they could be ready for parenting, teen will become more motivated to learn and use methods of pregnancy prevention in their current romantic relationships.

7. Assist students in identifying common risk and protective factors related to unplanned pregnancy.

Example risk factors include impulsivity, substance abuse, unhealthy relationships, promiscuity, unaddressed mental health issues. Protective factors would include healthy relationships, self-esteem, good communication, clear goals for the future. Conclude by helping teens strategize how they can address their risk factors.

We recommend anticipating the more challenging questions and issues students might pose. Students may ask for your personal opinion, or take an extreme stance, or be judgmental of classmates, or ask for help finding resources. With some forethought, you can be ready when these issues come up.

You can play a vital role in helping teens appreciate the risks of unplanned pregnancy and plan ahead so they can responsibly choose when and how to create a future family.

Please feel free to email me if you have any comments or questions: rrubenstein@eduparents.org. I’m always happy to assist with lesson-planning and tailoring programs to specific teachers’ needs. I’ve also provided a link to our instructional resources below in case they would be helpful to you.

Warmly,

Randi S. Rubenstein, M.S. Public Health

Founder, Executive Director

Educate Tomorrow’s Parents, Raleigh, NC

www.eduparents.org

1 “A white paper is an authoritative report or guide that often addresses issues and how to solve them. The term originated when government papers were coded by color to indicate distribution, with white designated for public access.” Policy Papers and Policy Analysis

Educate Tomorrow’s Parents Curriculum – Healthy Foundations for Future Families

If you are looking for ready-to-use curriculum, take a peek at our store on TeachersPayTeachers.com. Our materials delve into many planning and prevention topics for teens. They align with education standards for:

- Health Education

- Sex Education

- Family and Consumer Sciences

- Common Core

Each lesson includes a student lesson plan, slides, student workbook, and instructor guide.

Sources cited:

Guttmacher Institute 2014. American Teens’ Sexual and Reproductive Health. Fact Sheet. New York, The Guttmacher Institute. https://www.guttmacher.org/sites/default/files/pdfs/pubs/FB-ATSRH.pdf

Osterman MJK, Hamilton BE, Martin JA, Driscoll AK, Valenzuela CP. Births: Final data for 2020. National Vital Statistics Reports; vol 70 no 17. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. 2022. Accessed online: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr70/nvsr70-17.pdf

UNICEF (2001). A league table of teenage births in rich nations. Innocenti Report Card. Florence Italy. https://www.un-ilibrary.org/content/books/9789210601320

United Nations. United Nations Demographic Yearbook 2020. 71st issue. New York: 2021. Table 10. https://unstats.un.org/unsd/demographic-social/products/dyb/dybsets/2020.pdf – accessed April 2022

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Administration on Children, Youth and Families, Children’s Bureau, 2021 – The AFCARS Report – Preliminary FY 2020 Estimates as of October 4, 2021 https://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/documents/cb/afcarsreport28.pdf

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Administration on Children, Youth and Families, Children’s Bureau, 2021 – Child Maltreatment 2019. https://www.acf.hhs.gov/cb/research-data-technology/statistics-research/child-maltreatment .

The World Bank 2021. Adolescent fertility rate (births per 1,000 women ages 15-19). The World Bank: Data. United Nations Population Division, World Population Division. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.ADO.TFRT – accessed April 2022